JEDDAH – April 16, 2025. “That’s where they chop people’s heads off,” we used to whisper about Deera Square in the schoolyard. Almost three decades later, my mom, my husband Nat, and I drove past it on our way to Al-Balad. Whether those gruesome tales were based on truth or just schoolyard mythology, the square looked utterly ordinary in daylight. I was finally visiting the historic district I’d somehow never seen despite growing up just miles away.

The heat was already oppressive when we arrived. Empty alleys, shuttered shops. Most people visit in the evening when the weather cools, but I was trying to cram so much into our short few days in Jeddah. Everyone had been telling me to visit, especially now with all the restoration work.

I’d never been to Al-Balad. Growing up, it was just that place people mentioned when they needed specific frankincense for a wedding or a particular gold design for a dowry. Strange to be discovering it now at 44, playing tourist in the town I grew up in.

A port city’s architecture

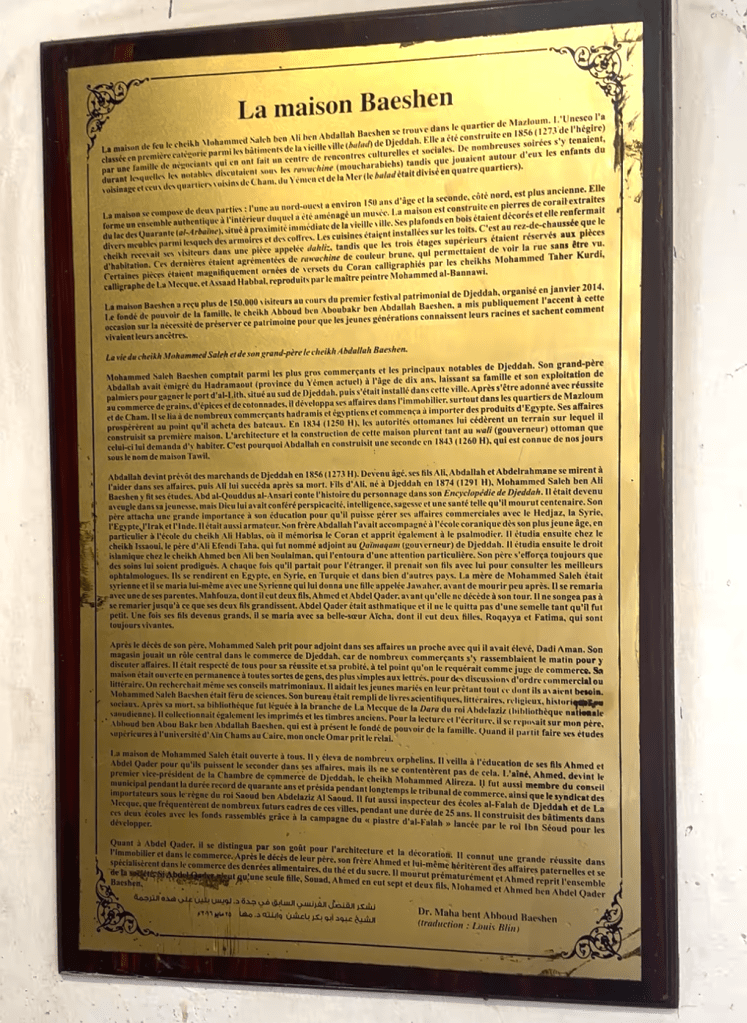

The houses of Al-Balad tell a different story than the desert fortresses of central Arabia. Built from compressed reef stone by merchant families who knew the sea better than the sand, these structures breathe with ocean air. Multi-story homes with carved wooden balconies called rawashin, designed to catch breezes and provide privacy before air conditioning changed everything.

From the 7th century onward, traders from Yemen, Egypt, and India settled here. They came for commerce but also displacement, opportunity, the promise of a better life. The architecture reflects this mix: a Yemeni window design here, Egyptian construction methods there. Wealthy merchant families maintained houses across the trade routes, Cairo, Bombay, Sana’a, bringing back influences that made Al-Balad distinct from the mud-brick buildings of Najd’s tribal heartland.

Walking these streets for the first time, I recognized something familiar in this blend of styles. These merchants understood what I’ve spent my adult life learning: how to belong to multiple places at once.

Unexpected discoveries

We ducked into the Tariq Abdulhakim Center when the sun became unbearable. I’d never heard of this Saudi composer, but that wasn’t surprising. Growing up in 90s Saudi Arabia, we weren’t learning about local composers in school. We were buying cassette tapes of Nirvana and Boyz II Men, obsessing over Mohammad Abdu’s latest hit or Amr Diab’s new video on satellite TV. Western and pan-Arab pop culture dominated our teenage years. Saudi cultural figures like Abdulhakim existed in a different sphere entirely, one that most of us never encountered.

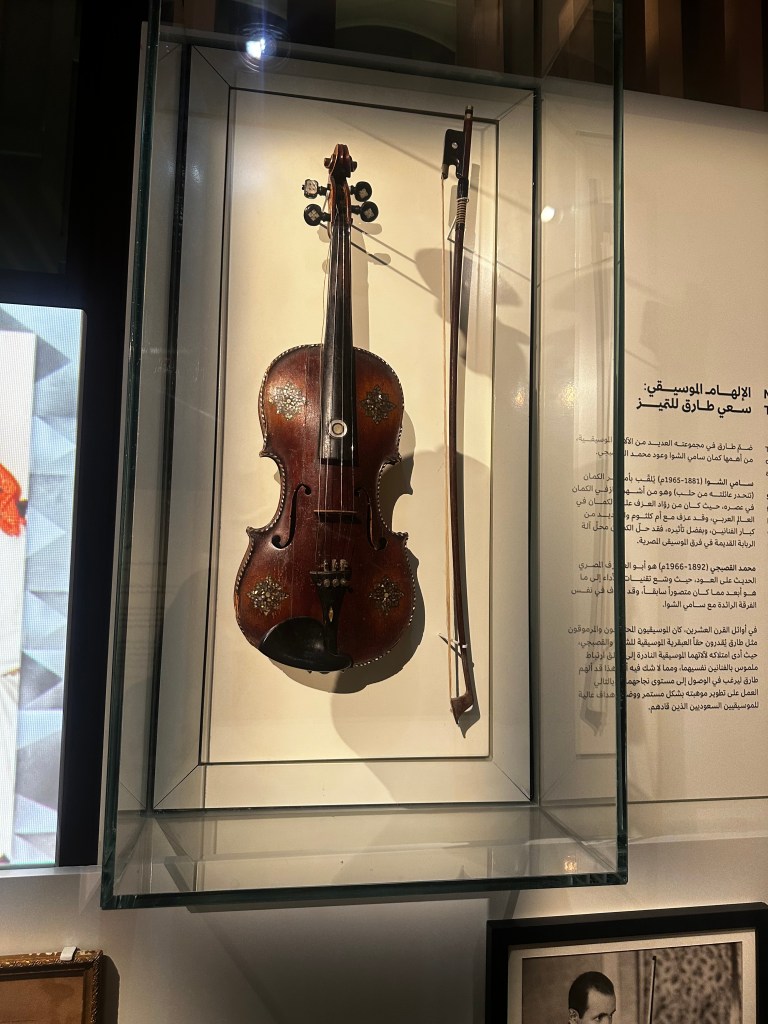

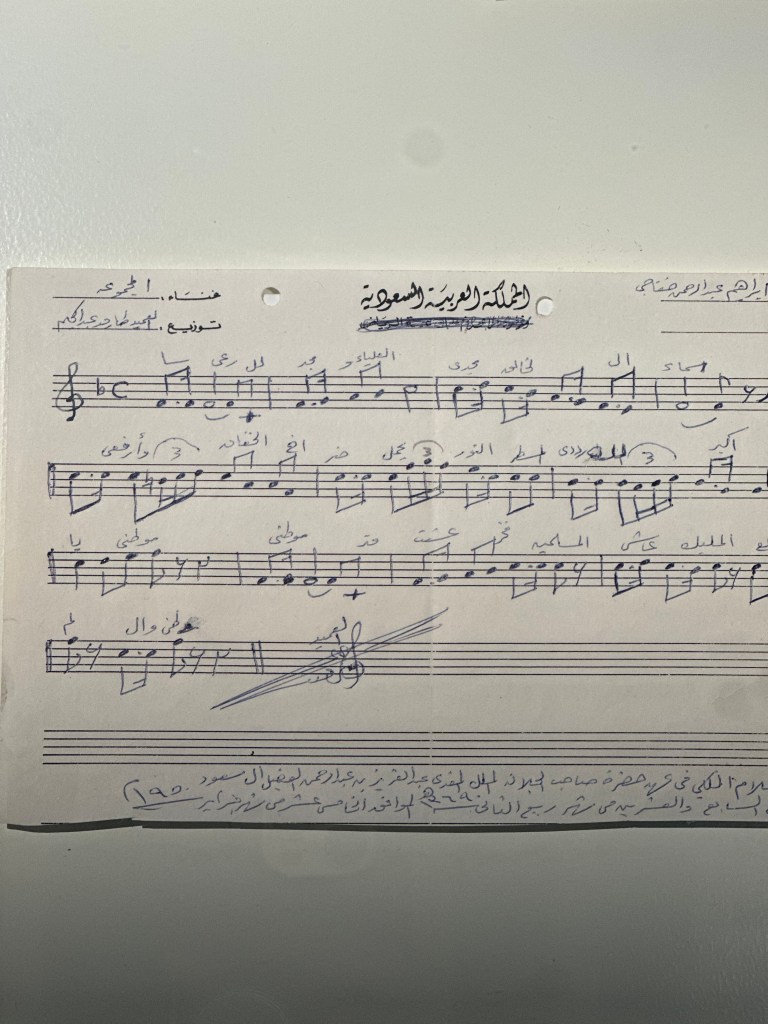

The museum guide, a young Saudi woman, welcomed us with that particular hospitality that makes you feel like an honored guest. She explained how Abdulhakim, known as the “General of Saudi Music,” had worked alongside legends like Umm Kulthum and Mohammed Abdel Wahab during the golden age of Arabic music in the 1950s and 60s, eventually composing Saudi Arabia’s national anthem.

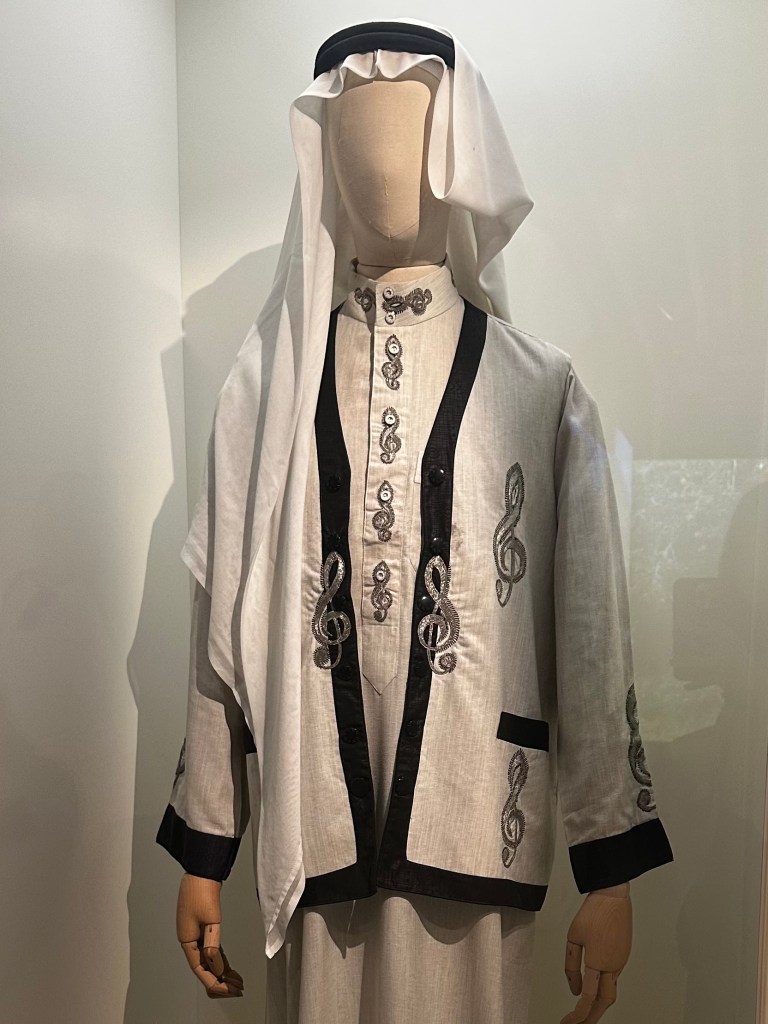

She showed us some of his original instruments, and at the end we saw a laser qanun, an electronic version of the traditional 72-string instrument, like a zither. Instead of plucking strings with fingerpicks, this futuristic instrument uses laser beams to create sound, with LED displays and electronic controls grafted onto the familiar trapezoidal form. It’s both ancient and space-age, a perfect metaphor for Saudi Arabia’s current transformation.

Here was yet another young woman in a public-facing role. It wasn’t surprising exactly, I’d known women like her in the female-only spaces I moved in growing up. Educated, well-spoken, cultured. Well-traveled, worldly despite the restrictions. Always soft-spoken but confident in their knowledge. But seeing them out in the world, sharing that knowledge with strangers in positions that would have seemed impossible during my childhood, that was new.

Coffee and revelations

After the museum, we needed somewhere cool to regroup. We found a café in a restored merchant house. I ordered a Spanish latte, curious after seeing it everywhere in Saudi coffee shops. Turns out it’s a Middle Eastern twist on Spain’s café con leche, sweetened with condensed milk and often spiked with cardamom. My mom ordered karkadeh.

Watching her sip the deep red drink, I asked for a taste and something clicked. “That’s just hibiscus,” I told Nat. The same tart, floral taste I’d been drinking in cocktails and fancy infusions back in Santa Cruz. I’d been consuming it for years without recognizing the karkadeh I’d dismissed as an old-fashioned Arab drink in my youth.

The economics of heritage

The empty streets made sense. No one visits Al-Balad in the heat of the day. The spice shops remained shuttered, the gold souk quiet. A few cats moved about, lounging in shadows or catching the cool air drifting from the few open shops.

The government has invested millions here as part of Vision 2030’s push to diversify beyond oil. When UNESCO designated Al-Balad a World Heritage site, it gave Saudi Arabia international validation for its heritage tourism ambitions. Banking on visitors wanting the “authentic” Arabia, the one that existed before glass towers and shopping malls. Restored buildings now house galleries and boutique hotels. Coffee shops occupy spaces where merchants once stored spices and textiles.

First-time visitor, lifetime resident

As we wandered about, the merchant families’ way of life felt unexpectedly familiar. Palestinian, born in Kuwait, raised in Jeddah, holding a Jordanian passport, now American, I understood their multiple residences, their children growing up between languages, their kitchens combining flavors from across trade routes. The patterns of diaspora and migration, people making homes wherever commerce, circumstance, or the search for safety and opportunity took them.

Racing the heat

By late morning, we retreated to the car. The old merchant families built for the climate; we just escaped to air conditioning.

Al-Balad’s restoration feels like Saudi Arabia getting ready to share itself with the world. Like that young woman in the museum stepping into public view. The patterns repeat: people have always moved between worlds, made homes in multiple places. The only difference now is that more of us do it, and more of us do it openly.

Leave a comment